The ocean floor holds secrets far beyond human imagination, and among its most enigmatic phenomena lies the "whale fall"—a term describing the carcass of a deceased whale sinking to the abyssal plains. Recent research has uncovered that these massive biological remnants serve as unexpected hotspots for viral evolution, particularly for bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria. Scientists now refer to these sites as "viral goldmines," where novel phage diversity flourishes in ways never before documented.

When a whale dies and descends to the seafloor, its body becomes a temporary oasis in an otherwise nutrient-poor environment. Scavengers, microbes, and other organisms quickly colonize the carcass, initiating a complex ecological succession that can last decades. But beneath this visible decay, a microscopic drama unfolds. Bacterial communities thrive on the decomposing tissues, and where bacteria go, their viral predators—phages—follow. The extreme conditions of the deep sea, combined with the unique biochemical milieu of a decaying whale, create a perfect storm for phage diversification.

A Hidden World of Viral Innovation

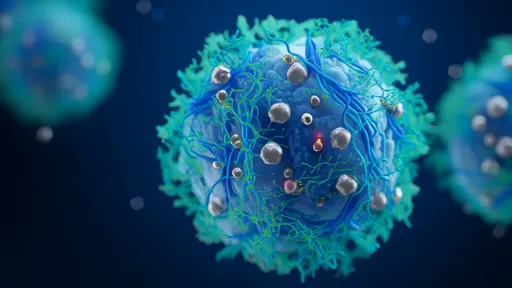

Deep-sea phage populations discovered at whale falls exhibit genetic signatures unlike anything found in surface waters or even other marine environments. Metagenomic analyses reveal that these viruses possess novel genes encoding enzymes capable of breaking down complex organic compounds—tools that may have evolved specifically to exploit the lipid-rich, protein-heavy environment of a rotting cetacean. Some phages even carry auxiliary metabolic genes, hijacking bacterial machinery to optimize their host's metabolism for viral replication.

The pressure to adapt in this extreme habitat drives rapid viral evolution. With bacterial hosts competing fiercely for limited resources, phages must constantly innovate to maintain their infectivity. This arms race between bacteria and viruses leads to an explosion of genetic diversity, with some whale fall phages showing less than 50% genetic similarity to known viral sequences in databases. Researchers describe the phenomenon as "evolution on fast-forward," with viral genomes reshuffling at unprecedented rates.

Ecological Implications Beyond the Abyss

These discoveries challenge long-held assumptions about viral distribution and evolution in marine ecosystems. Traditionally, scientists believed that phage diversity peaked in nutrient-rich surface waters where bacterial hosts abound. Whale falls turn this paradigm upside down, demonstrating that extreme, resource-limited environments can become crucibles of viral innovation. The phages emerging from these sites may play crucial roles in deep-sea carbon cycling, breaking down complex molecules that would otherwise remain locked in the carcass for centuries.

Moreover, whale fall phages could represent an untapped reservoir of biotechnological potential. Their unique enzymes, evolved to function under high pressure and low temperature, may have applications in industrial processes ranging from biofuel production to pharmaceutical development. Some researchers speculate that these viruses might even harbor novel antimicrobial compounds, offering clues in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Unanswered Questions and Future Exploration

Despite these breakthroughs, fundamental mysteries remain. Scientists don't yet understand how phage populations transition between different stages of whale fall succession, or whether certain viral lineages specialize in particular microhabitats within the carcass. The role of viral lysogeny—where phages integrate into host genomes—versus lytic cycles in these environments remains poorly characterized. Furthermore, researchers have barely scratched the surface of viral diversity at whale falls, with sampling limited to a handful of sites worldwide.

Advanced technologies like autonomous deep-sea samplers and long-term observatories may help unravel these mysteries. Some research teams are developing specialized equipment to collect viruses from whale falls without disturbing their delicate ecological balance. Others are employing cutting-edge single-cell genomics to study phage-host interactions at unprecedented resolution. As these tools mature, they promise to reveal even more surprising facets of this underwater viral renaissance.

The discovery of whale falls as viral biodiversity hotspots underscores how much we have yet to learn about Earth's largest ecosystem. These deep-sea events, once thought to be biological oddities, are now recognized as engines of microbial and viral evolution. As climate change and human activities alter ocean ecosystems, understanding these processes becomes increasingly urgent—not just for pure scientific knowledge, but for the potential applications they may hold for medicine, industry, and environmental conservation.

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025