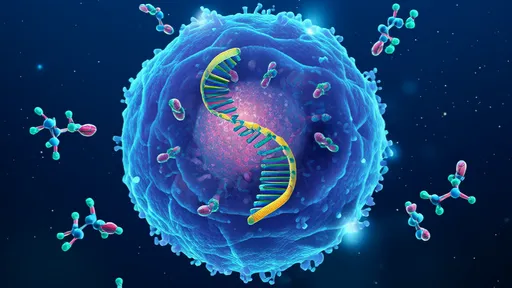

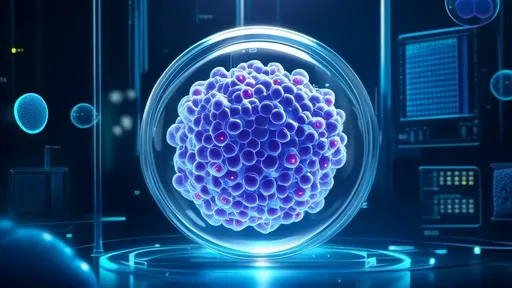

In a groundbreaking development at the intersection of nanotechnology and gene editing, scientists have engineered a self-propelled DNA "nanocar" capable of delivering CRISPR-Cas9 payloads with unprecedented precision. This biomolecular vehicle, constructed entirely from folded DNA strands, represents a paradigm shift in targeted therapeutic delivery—navigating the bloodstream like a microscopic courier programmed to seek specific cell types. The innovation lies not just in its cargo, but in its autonomous movement powered by enzymatic fuel, enabling it to traverse biological barriers that traditionally stymie drug delivery systems.

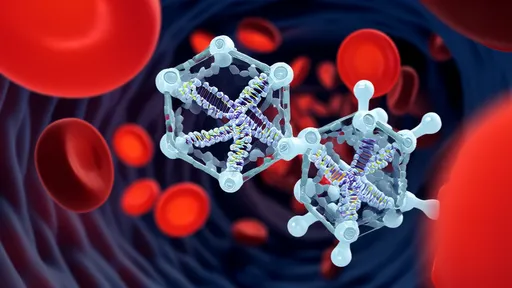

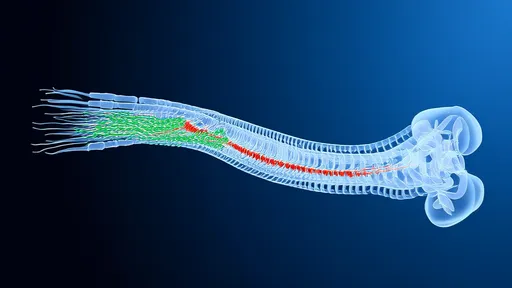

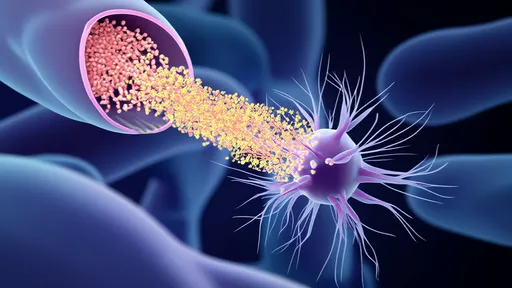

The nanocar's chassis, assembled through DNA origami techniques, forms a robust yet flexible structure measuring mere nanometers across. What sets it apart from passive delivery vehicles is its incorporation of ATPase-based molecular motors, which convert chemical energy into mechanical motion. Researchers at the BioNano Engineering Consortium observed these vehicles moving at speeds of up to 0.8 micrometers per minute in vitro—remarkable for synthetic nanostructures. "It's like giving CRISPR a GPS and a Tesla engine," remarked Dr. Helena Voss, lead author of the study published in Nature Nanotechnology. "The DNA framework provides both the navigation system and the propulsion."

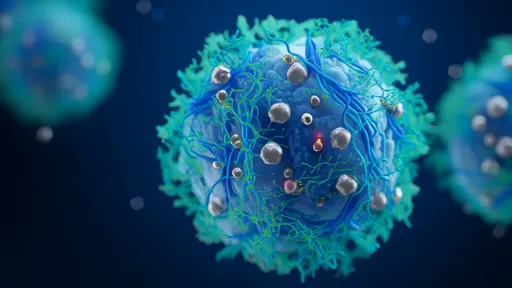

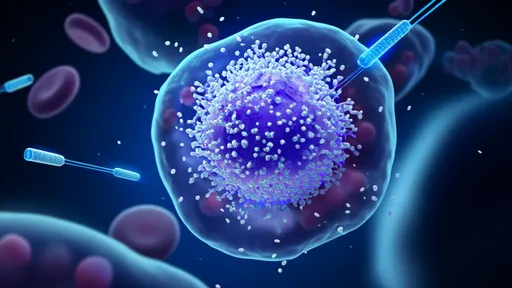

Targeting specificity is achieved through aptamer-based "homing beacons" that extend from the nanocar's surface like biological antennas. These single-stranded DNA fragments bind selectively to protein markers on target cells, with recent trials demonstrating 92% accuracy in distinguishing cancerous from healthy cells in glioblastoma models. Once docked, the vehicle undergoes a conformational change triggered by pH shifts near cell membranes, releasing its CRISPR machinery with surgical precision. This addressable delivery circumvents the off-target effects that plague conventional viral vector methods.

The CRISPR payload itself has been ingeniously packaged within protective DNA nanocages that remain stable during transit but unravel upon encountering specific intracellular conditions. Early experiments targeting the VEGFA gene in tumor vasculature showed a 70% reduction in off-site edits compared to lipid nanoparticle delivery. Perhaps most impressively, the nanocars exhibit swarm-like behavior when deployed en masse, with enzymatic communication between vehicles preventing redundant targeting of the same cell—a feature inspired by bacterial quorum sensing mechanisms.

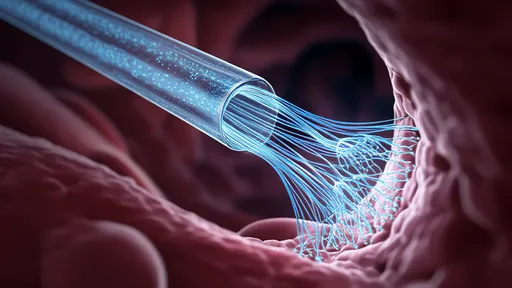

Challenges remain in scaling production and addressing immune system recognition, though the team has made progress by incorporating human albumin coatings that reduce macrophage uptake. Preclinical trials in non-human primates are slated to begin next quarter, focusing on hereditary retinal diseases where precise CRISPR delivery could prevent photoreceptor degeneration. If successful, this technology may eventually treat conditions ranging from genetic disorders to stubborn viral infections—all via nature's own molecular building blocks repurposed as therapeutic transporters.

Beyond medicine, the implications extend to basic research. These mobile nanosystems allow real-time observation of gene editing dynamics previously obscured by delivery inefficiencies. As Professor Carlos Mendez of the Institute for Molecular Robotics notes: "We're not just building better delivery tools—we're creating observatories to watch CRISPR's molecular ballet unfold." With refinements underway to incorporate RNA interference cargoes and multi-gene editing suites, DNA nanocars may soon revolutionize how we engineer biology at its most fundamental level.

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025