In the dense rainforests of Central and South America, a remarkable agricultural system has thrived for over 50 million years—one operated not by humans, but by tiny six-legged farmers. Leafcutter ants (Atta and Acromyrmex species) have developed sophisticated fungal cultivation techniques that put many human agricultural practices to shame. Recent research reveals how these insects employ what scientists are calling "swarm AI" to collectively optimize their fungal gardens through decentralized decision-making.

The leafcutter ant's agricultural enterprise begins with its namesake behavior—precisely cutting fragments from living plants. But this is no random defoliation. Each ant acts as a sensory node in a distributed network, assessing vegetation quality through chemical cues and physical properties. What appears as chaotic cutting actually represents a continuous optimization process where the colony samples diverse plant sources to maintain optimal nutritional balance for their fungal cultivars.

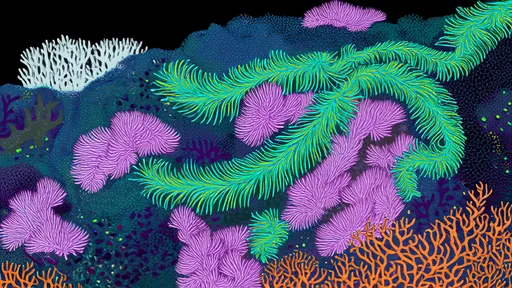

These ant farmers don't actually eat the leaves they harvest. Instead, they process the vegetation into a compost that feeds their true crop—a specialized fungus (Leucoagaricus gongylophorus) that has co-evolved with the ants for millennia. The fungus serves as the colony's primary food source, producing nutrient-rich swellings called gongylidia that the ants harvest. This mutualistic relationship represents one of nature's most ancient and successful agricultural systems.

What's particularly fascinating is how colonies adapt their harvesting strategies. Research shows that when presented with novel plant species, a colony will initially sample small quantities while carefully monitoring fungal growth responses. Worker ants tending the fungal gardens serve as living biosensors, detecting subtle changes in fungal health through chemical and tactile cues. Information about substrate quality spreads through the colony not via centralized control, but through distributed feedback mechanisms.

The decision-making process resembles a biological version of artificial intelligence algorithms. Individual ants function like processing units in a neural network, each contributing local information that collectively informs the colony's harvesting choices. When certain plant materials prove beneficial to fungal growth, recruitment to those sources increases through pheromone trails. Conversely, harmful substrates are abandoned through the absence of positive reinforcement—a classic case of distributed optimization.

Scientists have identified several remarkable parallels between ant colony decision-making and machine learning systems. The colony's sampling strategy mirrors the "explore-exploit" algorithm in AI—balancing experimentation with new plant sources against exploitation of known good substrates. This dynamic balance allows colonies to adapt to changing environments while maintaining stable fungal production.

The agricultural sophistication extends to waste management. Leafcutter ants maintain specialized refuse chambers where they deposit spent substrate and potentially harmful microbes. These chambers are carefully positioned away from fungal gardens and nurseries, demonstrating an understanding of disease prevention that rivals human agricultural practices. Some species even employ antibiotic-producing bacteria to protect their fungal crops, creating a multi-tiered symbiosis.

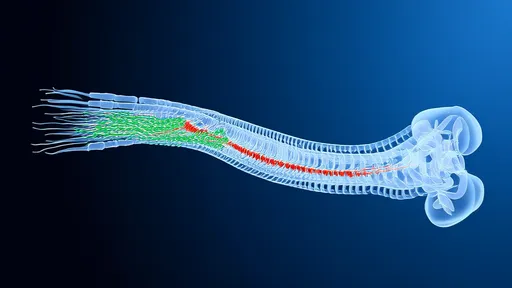

Recent experiments using micro-CT scanning have revealed the intricate architecture of fungal gardens. The ants arrange the compost in a specific spongelike structure that optimizes air flow and humidity—critical factors for fungal health. This architecture emerges from simple rules followed by individual workers, yet produces a highly efficient macro-scale environment.

What can human agriculture learn from these tiny farmers? Researchers suggest that ant colonies demonstrate principles of resilient, decentralized agricultural systems. Their continuous small-scale testing of new substrates while maintaining core food production provides a model for sustainable innovation. The absence of centralized control in ant colonies makes their agricultural system robust to individual failures—a feature that human smart farming systems might emulate.

The leafcutter ant's agricultural success stems from a perfect integration of individual simplicity and collective intelligence. Each ant follows basic behavioral rules, but together they create a sophisticated farming operation that has survived geological epochs. As we face challenges of food security and sustainable agriculture, these ancient insect farmers may hold valuable lessons about collective problem-solving and ecological harmony.

Ongoing research aims to decode the precise communication mechanisms that allow such precise coordination. Scientists are particularly interested in how error correction happens in the system—how colonies identify and rectify poor harvesting decisions. Early evidence suggests a form of "social proofing" where ants preferentially follow trails that show high traffic, creating positive feedback loops for optimal sources.

The agricultural practices of leafcutter ants represent one of nature's most extraordinary examples of distributed intelligence. Without blueprints, leaders, or conscious planning, these tiny creatures maintain complex agricultural systems that sustainably feed colonies of millions. As we develop smarter agricultural technologies, perhaps the most advanced AI system we should study is the one that's been operating successfully in tropical forests for tens of millions of years.

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025