In a groundbreaking advancement for transplant medicine, researchers have turned to nature’s playbook to solve one of the most persistent challenges in organ transplantation: immune rejection. Drawing inspiration from biological systems that evade detection, scientists are developing "invisibility cloak" coatings for donor organs using biomimetic materials. These innovations could revolutionize transplant outcomes by shielding foreign tissues from the host’s immune system without the need for lifelong immunosuppressive drugs.

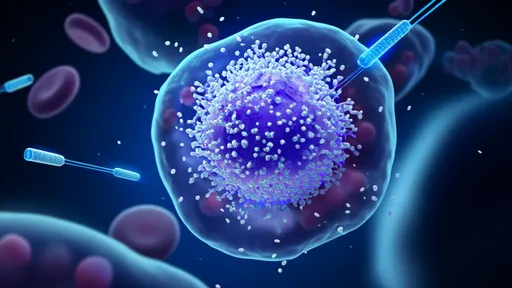

The human immune system is exquisitely tuned to identify and destroy anything it perceives as foreign—a defense mechanism that becomes a hurdle when introducing donor organs. Traditional approaches rely on powerful immunosuppressants, which come with severe side effects, including increased susceptibility to infections and cancer. The new approach, however, seeks to deceive the immune system altogether. By coating organs with bioengineered materials that mimic the body’s own cellular signatures, researchers aim to create what some call "immunological camouflage."

Nature’s Blueprint: Learning from Stealth Organisms

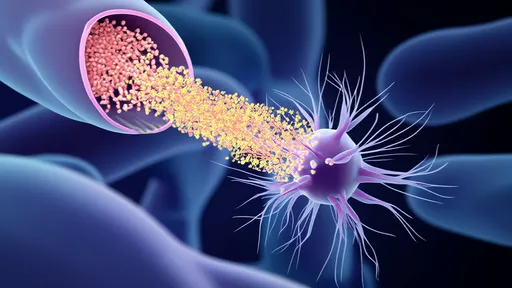

This technology takes cues from organisms that naturally evade immune detection. Certain parasites, such as the Schistosoma flatworm, and even some cancers, produce surface molecules that trick the host into tolerating their presence. Similarly, the developing fetus, which carries foreign paternal antigens, avoids rejection by the mother’s immune system through sophisticated biological disguises. Scientists are now reverse-engineering these strategies to create synthetic coatings that replicate such stealth properties.

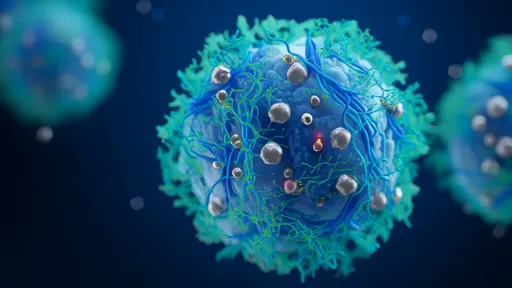

One promising material under investigation is a hydrogel infused with proteins derived from cell membranes. These proteins display "self" markers that signal "friend" rather than "foe" to immune cells. Early experiments with pancreatic islet cells—a common transplant target for diabetes treatment—have shown remarkable success in animal models. Coated islets survived for months in non-immunosuppressed hosts, functioning normally without triggering an attack.

Engineering the Perfect Cloak: Challenges and Breakthroughs

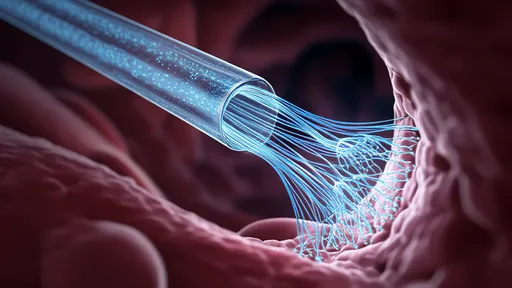

Creating an effective invisibility coating is no simple feat. The material must adhere securely to the organ’s surface, withstand blood flow and mechanical stress, and remain functional for years. Researchers at MIT recently unveiled a polymer-based "nanoshield" that binds to tissue surfaces through molecular hooks. Unlike previous attempts, this design allows nutrients and oxygen to pass through while blocking immune cells and antibodies—a critical feature for long-term viability.

Another hurdle is ensuring the coating doesn’t interfere with the organ’s function. For example, a kidney’s filtration capacity or a liver’s metabolic activity must remain unimpaired. Teams in Germany have addressed this by developing porous, ultrathin coatings that mimic the extracellular matrix—the natural scaffolding around cells. These coatings not only hide the organ but also promote tissue regeneration, reducing post-transplant complications.

Beyond Transplants: A Universal Platform for Cell Therapies?

The implications extend beyond whole-organ transplants. Stem cell therapies for conditions like Parkinson’s or spinal cord injuries often fail because introduced cells are rapidly cleared by the immune system. A biomimetic coating could protect these cells, allowing them to integrate and repair tissue. Early-stage trials are underway for coated stem cells in heart repair, with preliminary data showing reduced inflammation and improved cell survival rates.

Critics caution that the technology isn’t without risks. An overly effective cloak might prevent the immune system from attacking legitimate threats, such as infections within the transplanted tissue. Researchers counter that their designs include "safety switches"—materials that degrade in response to specific enzymes, allowing controlled immune access if needed. This balance between stealth and safety remains a key focus of ongoing studies.

The Road Ahead: Clinical Trials and Ethical Considerations

Human trials for coated organs could begin within the next three to five years, pending regulatory approvals. The first candidates will likely be pancreatic islets or partial liver segments, where the risks are lower compared to heart or lung transplants. Ethicists are already debating whether this technology should prioritize life-saving organs or focus first on improving quality of life—for instance, by enabling insulin-free diabetes management.

If successful, this biomimetic approach could render organ matching obsolete, dramatically expanding donor pools. A liver from a pig or even a bioengineered source might become universally transplantable with the right coating. Such a future would rewrite the rules of transplantation, turning what was once science fiction into medical routine.

As labs worldwide race to refine these stealth materials, one thing is clear: evolution spent millions of years perfecting immune evasion, and science is now learning to borrow those secrets—one molecule at a time.

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025