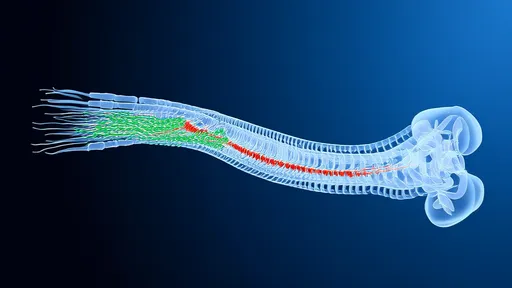

Chronic pain remains one of medicine's most perplexing challenges, affecting millions worldwide with often devastating consequences. For decades, researchers have grappled with understanding how the nervous system processes and perpetuates persistent pain signals. Now, a groundbreaking study published in Nature Neuroscience has mapped specific spinal cord circuits responsible for different types of chronic pain, offering unprecedented insights into this debilitating condition.

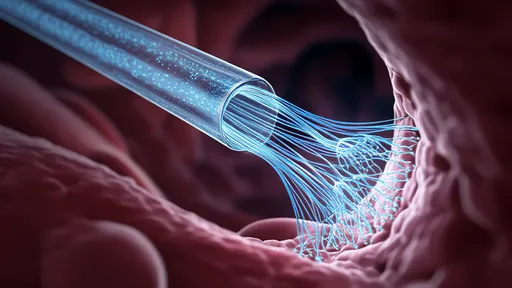

The research team employed advanced genetic labeling techniques combined with optogenetics to trace pain pathways with remarkable precision. Their work reveals that distinct neural populations in the spinal cord process mechanical versus thermal pain signals, challenging previous assumptions about pain processing uniformity. This discovery fundamentally alters our understanding of how chronic pain becomes entrenched in the nervous system.

What makes these findings particularly significant is their potential to revolutionize pain treatment approaches. Current pain medications often fail to distinguish between different pain modalities, leading to suboptimal outcomes and significant side effects. The newly identified "pain maps" suggest that targeted therapies could be developed to address specific pain types without affecting other sensory functions.

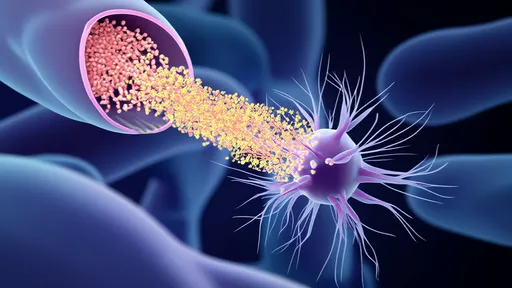

The study focused on lamina I of the dorsal horn, a critical relay station for pain signals entering the spinal cord. Using transgenic mice models, researchers identified two separate neuronal populations: one that primarily responds to mechanical stimuli (like pressure or pinch) and another specialized for thermal detection. These populations project to different brain regions, creating parallel pain processing streams.

Perhaps most intriguingly, the team found that chronic pain states cause molecular and functional changes specifically within these dedicated circuits. In neuropathic pain models, the mechanical pain pathway showed heightened sensitivity and spontaneous activity, while the thermal pathway remained relatively unchanged. This specificity explains why some chronic pain patients report extreme sensitivity to touch but normal temperature perception.

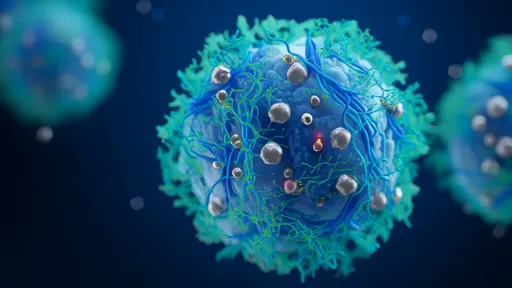

The implications extend beyond basic science. Pharmaceutical companies have already expressed interest in developing drugs that target these specific circuit components. Unlike broad-spectrum painkillers that dampen all neural activity, precision medications could silence pathological pain signals while preserving protective acute pain responses and normal sensory function.

Clinical neurologists have greeted these findings with cautious optimism. Dr. Elena Vasquez from Massachusetts General Hospital notes, "For the first time, we're seeing clear anatomical distinctions that could explain why patients experience different chronic pain phenotypes. This gives us concrete targets for both pharmacological and neuromodulation therapies."

The research also sheds light on why some pain treatments work better for certain individuals than others. A patient with predominantly mechanical allodynia might respond beautifully to a therapy targeting that specific pathway, while another with thermal hyperalgesia might require different intervention. This level of diagnostic precision was previously unimaginable in pain medicine.

Looking ahead, the team plans to investigate whether similar circuit specificity exists in human spinal cords and how these pathways might differ across various chronic pain conditions. Early results from postmortem tissue studies appear promising, showing analogous neuronal populations in human dorsal horn tissue.

As research progresses, the hope is that these neural maps will lead to more effective, personalized pain management strategies. For the millions suffering from chronic pain, these findings represent more than scientific advancement—they offer tangible hope for reclaiming lives from persistent pain's relentless grip.

The study's senior author, Dr. Michael Chen, reflects on the work's broader significance: "We've moved from viewing chronic pain as a generalized state of nervous system hypersensitivity to understanding it as a precise malfunction of specific neural circuits. This paradigm shift opens entirely new therapeutic possibilities that we're only beginning to explore."

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025